Kilimanjaro

May 4, 2020

No, this is not fiction. This is how it happened. It is my own itihasa. He died in 2003, on the summer solstice, the last day of Uttarayanam. And today is his birthday.

Kilimanjaro

By Rajeev Srinivasan

“I used to keep all your letters because I thought you’d become famous,” my father said to me once, “but one day I realized you wouldn’t.” That was the most hurtful thing my father ever said to me, and he didn’t even say it with spite. It was simply matter of fact, and that hurt more than anything else because it was the brutal truth. I thought of the pile of letters from my parents that I have saved, old blue aerograms bundled together with rubber bands. And of the ten years in my life that have passed, unrecorded and unmourned, while I waited, and I missed the starting gun.

When I was a child, my father never punished me, but once. I cannot remember what I did, but I was about eight. I ran, hoping to outrun him, but he chased me around our old house, the one that we later sold to the timber merchant. He struck me, once or twice. But then he was remorseful and took me out and bought me comic books.

But mostly I could speak to him as a friend. Not like my mother, who was the disciplinarian in the family, and who commanded respect and a certain distance. And he would talk at length about his favorite liberal causes, and socialism, and Gandhism. My class teacher once said to me when I was a teenager, “You are lucky to have such an enlightened father.” My father had just come and spoken at my school, I can’t remember the topic, but it was probably something to do with Gandhism.

I said to friends when I first came to America that my letters to my parents were so very different, the one to my mother formal and informative and respectful, the one to my father more chatty and more like something I would write to a favorite uncle. It didn’t occur to me until later that my mother and I do have much in common, but that she simply did not have the time to pay attention. She had to work and look after my father, and she had no time for her children, as she said to me ruefully, years later.

When I was a very small child, my father bought a radio for me, “so you could listen to music.” We had that ancient GEC radio for many years, big and boxy with old-fashioned, glowing electron tubes, and it must have cost him a princely sum in those days. It had little slots in the back for air to come in to cool the tubes. I used to worry about the geckos that would casually squeeze themselves in and out of the slots: would they fry themselves and destroy the radio? Last year, when I went home, I found that old radio was gone. I missed it; I remembered watching the green magic eye and trying to tune in the BBC and Radio Moscow and the Voice of America.

Our house has always been awash with books and my father was constantly reading, and writing. He wrote fiction when I was little, and he translated books into Malayalam. I read novels from his bookshelf, voraciously, and without plan: man-eaters of Kumaon, the story of Genji, Marcel Pagnol’s childhood.

I wished he would write heartbreaking stories, of poor laborers and brave communists and feudal landlords, but he would not. He preferred to write essays, and he read boring, arcane journals. Once, when I was upset, I told my father that he was a “mere reactionary”. I didn’t actually know what a reactionary was, I just knew it was a bad thing to be.

Much later, I begged him to write a novel about his ancestral village; the one with the predatory old women and the silent, gentle old men. About his uncle, the nationalist; about his great-uncle, the journalist. Every year when I visit he tells me about yet another of his old relatives who has passed away. I say: “It’s their memories you must capture-you can’t just let them die! I’ll come with you and I’ll bring a tape recorder and record what they remember!” But we never do. I think he is afraid of fiction now. Or maybe he is just lazy. Fiction is so much harder to write.

Sometimes my father and I drove up to the prosperous rubber town, so he could attend a meeting of the writer’s co-operative he was a director of. We stopped at a roadside tea stall. I wanted a batter-fried banana. The piping-hot treat was delicious, golden-brown, slightly caramelized at the edges, with a sprinkling of sugar, and I liked the smoky interiors of the little thatched lean-tos. They served tea, frothy, cooled dexterously in a yard-long stream between two metal tumblers. I was not to tell my mother, who did not trust such places. “Our little secret,” my father said, conspiratorially.

My father has a keen sense of smell; and he would embarrass me sometimes when I came down for breakfast. He would look up, take a sniff or two with his large, fleshy nostrils, and then ask me suspiciously, “Did you brush your teeth today?” I would protest, innocence bruised. And when the jackfruit or mangos get ripe in the yard, he is always the first to know about it.

My father used to like photography, with his Yashica, which his wealthy uncle from Singapore had given him. He was patient, and he demanded patience of his models. He would look down through the lens of the old double-lens camera, adjust our poses and the camera angle, and fiddle around interminably before he finally clicked. I realized later that it was an act of self-affirmation. He remembered his youth, when he was poor, and he wanted to record his rise to the middle class. As a youngster, he worked in the Railways, in sweltering Tamil Nadu towns, and when we traveled by train, he always chatted with the ticket examiner, to inquire after old acquaintances. He saved enough money to put himself through college, he was a journalist too; and he was a good orator and became head of the student union. But it didn’t interest him much, and he resigned over a matter of principle; and he never took advantage of his contacts.

When I was in high school, my father had to get me out of trouble with the police. I violated a simple rule, that of riding my bicycle with no lights on; but when questioned by the police, I lost my head. I gave them a false address, and, on further questioning, it was obvious that I had no idea about the neighborhood I mentioned. They took me to the station, and I waited, ashamed. I was a good child in general, and I was mortified. But my father didn’t say much when he came to get me. The inspector was an acquaintance of his, perhaps one of his old students, so it was a double humiliation for him.

But he didn’t say anything at all. It was as though this were normal – bailing his errant son out of trouble. No histrionics, no recriminations. I waited for the other shoe to drop, but it never did. Maybe he realized the humiliation was enough to teach me a lesson. I never got into trouble again with the police.

One warm summer day when I was a teenager, I lost his Rayban sunglasses. They were his pride and joy. Some friend of his had brought them from London. I lost them somewhere; I think they were stolen. Later, when I moved to America, I brought him back expensive sunglasses. But somehow they were never as good as the old pair I lost. After all, he had been a younger man then, and had cared more for these little vanities.

Father used to indulge in a couple of other small luxuries – tennis and an occasional drink. I would always bring him tennis gear, clothes and racquets and shoes; single-malt whisky, and sometimes cognac. It is easy to buy gifts for him, because he always tells me exactly what he wants – men’s toiletries or a book by Noam Chomsky or a typewriter. Now he has given up his tennis, but he still likes an occasional drink. He gets expansive when he drinks too much, and he tends to repeat himself. It is a shame he is not playing tennis anymore: he looked smart in his whites, bounding about with enthusiasm. He had an eye for my good T-shirts.

I kept asking him to come visit me. I picked him up at the airport in Boston the first time he came to America. He seemed smaller than I remembered, a middle-aged man in a not-so-fashionable beige safari suit. Gray hair thinning on the crown. Clean-shaven. Heavy-rimmed, professorial glasses. A brown man of average height, small compared to all those towering white people; somewhat apprehensive of this strange country, holding on nervously to his briefcase and walking out from immigration, pushing his luggage trolley and looking around for me. And then when he left, looking back and waving again and again as he disappeared down that long tunnel.

He used to think all Americans were literary-minded, for he had only met scholars amongst them before, and he had taught American literature for years. He liked Cambridge, and later, Stanford; but he really preferred Britain. He found America too brash. He felt more comfortable when my uncle in Britain took him to see the Lake District and Shakespeare’s home. Once I took him to see Stonehenge, and he was not impressed. “Why, there are more interesting piles of rocks in Kerala,” he said.

As my stay in America grew longer, my father started asking questions: when would I come back? After five years, I said. Then it was ten. I drifted along, aimless. Then came the question of marriage. He wanted me to marry someone who would be kind to me, he said. Not having much of a reason to say no, I agreed.

So he found someone. She was rich, too. And it was a complete disaster. We got divorced. It took all of us years to recover from the recriminations and the allegations. I realized we never really talked, not as father and son, except in exchanging pleasantries as though we were polite strangers. We were afraid to tell the whole truth, and we assumed things about each other.

I hadn’t been able to tell my father about my need to be free, to be on my own, self-reliant, self-sufficient and self-absorbed. I dreamt pleasant dreams about the Serengeti, about the thundering herds of wildebeest; but most of all, about towering Kilimanjaro, standing alone, in splendid isolation, a solitary peak in the middle of a vast, flat continent. I couldn’t express my need to be by myself, to be free. I wanted to tell him about being a loner, about the Steppenwolf, but he didn’t want to listen.

And he has never understood. My mother did, though; I discovered that I had more in common with her than I had thought. She retired from her college and she and I would talk about history, which she had taught for many years.

I have returned to Kerala, dutifully, at least once a year, and mostly in the winter like all the other Indians, saving up those two weeks. One year, I fell ill at home; and my precious vacation was ruined. But all of a sudden, lying there under a stuffy mosquito net, it occurred to me that time was passing me by. That I was no longer a carefree youth. And that I needed to be home again: I was weary of my travels. I wanted to be with my parents.

I remembered the time I went on pilgrimage to Sabarimala, years ago, when I was a teenager. I trekked up the steep hill, peaceful during June showers, and it was quiet because it was out of season. I walked alone, barefoot, up trails through heavy forest, and the pebbles were sharp underfoot. Now and then a fellow-pilgrim, bearded and black-clad, came down the path, and we smiled as we passed each other by; some said, “Swami saranam!”.

The rain, drizzle really, felt cool on my skin: I was glad because it made the climb less tiring. But I had to watch for leeches: you wouldn’t know if they attached themselves to your legs and stuck on, fattening on your blood until you applied salt to them to force them to let go. From far off came the sound of a waterfall. Now and then, the cry of a howler monkey echoed through the canopy, and there was an occasional bird, but otherwise it was still. I remembered the tigers and elephants that punish non-observant pilgrims. There was the heavy scent of wet earth and of vegetation: the forest’s breath, amplified by the rain.

And then I reached the sanctum, at dusk. I climbed the eighteen steps of gold. The tiny sanctum sanctorum, the garbha-grha, was much smaller than I expected. The image of the Lord, that I had seen a thousand pictures of, was small, too: serene, unusual, seated, and surrounded by the flickering light of oil lamps. Incense and the smell of coconut-oil wafted through the air. Bodies pressed up against me; I had to brace myself to not lose my footing. The praises of the Lord echoed in the air. The tall, bearded priest distributed prasadam, and it was sweet and tangy on my tongue.

And then, quite unexpectedly, I caught a fleeting, shattering, inexpressible glimpse of something – of a doorway opening in the heavens, of God’s Grace, of Infinity. Of indescribable Bliss, sat-chid-ananda. I thought to myself, I want to die now, I want to die in this moment, for I fear I shall never experience this ecstasy again.

I stood paralyzed. But the moment passed. I rationalized it. Perhaps it was the exhaustion from the long and difficult trek. Perhaps it was a self-fulfilling expectation, the stories of sanctity that I had heard from my elders. Maybe it was the vratam, the penance of forty-one days. I found a hundred rational reasons for that feeling I could not quite put into words. Faith made me uncomfortable. Living in America, I had become dismissive of the gods of my ancestors.

But now, lying in my sick-bed, it came back to me, that vision of wonder, that instant when I had had a tantalizing vision of something much greater than myself, that marvel that I had experienced. I just knew that the Lord of Sabarimala was calling me, and I had to respond.

Slowly, I rediscovered my faith; religion and motherland began to be intertwined in my mind. I read Sri Aurobindo, and he spoke for me: nationalism is the defense of the sanatana dharma. I understood that I missed India with a fierce passion. And that I cared deeply about Indian history. I began to see that I was an exile, and that America no longer excited me. I used to think this was God’s own country, once upon a time.

I wanted to tell my father about my rediscovery of my identity. But he would not listen, because for him religion is anathema. And my self-definition involved me being an Indian and a Hindu. We argue and shout now, whenever we talk about this: he, former leftist, agnostic, and cynical; and me, zealous, theist, believer. So we prefer to talk about what we agree on: an intense nationalism.

And then I saw the film “Piravi” (The Birth), at the San Francisco Film Festival. It was about an old man, a teacher, searching for his son, who disappeared while in police custody. I noticed with amazement that in his hostel room, the son had a huge, enlarged portrait of his father. I too have huge portraits that I took myself: of my father, mother and sister, filling a wall in my study.

Later, the old man realizes his son would never return; going home, he slips and falls in the rain; he has no son to help him up, and so a kind stranger, the ferryman, helps him up and back to his home. Tears streamed down my face, for my father too has no son to help him: I am in America. I have never wept at a film before or after that. I am a film buff, I have seen hundreds of moving films, but this one, alone, spoke to me.

I saw the film again. It begins with an invocation from the Kaushitaki Upanishad; a dying man bequeaths his life to his son. The son accepts each of his gifts.

“My speech in you I would place”. “Your speech in me I take.”

“My sight in you I would place.” “Your sight in me I take.”

“My mind in you I would place.” “Your mind in me I take.”

“My deeds in you I would place.” “Your deeds in me I take.”

“My vital breath in you I would place”. “Your vital breath in me I take.”

“May glory, luster and fame delight in you.” “Heaven and desires may you obtain.”

And from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, “Whatever wrong has been done by him, his son frees him from it all… By his son, a father stands firm in this world.”

I cried again at the film.

My father is so much a part of me, I thought, even though we refuse to communicate. And even though we are matrilineal. I tried to tell him how I felt, but I could not find the words. He has never seen the film himself and even if he did, it might not resonate with him as it did with me.

I understood that my Kilimanjaro is borrowed from him. My sister once said to my mother, “Father thinks of nobody at all; and my brother only thinks of himself.” She didn’t say it with rancor. Perhaps she was right.

I go home as often as I can. My father is in his seventies. “I am living on borrowed time,” he says. “Why don’t you come back here and live with us?”

I try to explain that there I would not be able to do anything that I am trained for. I would have to go live in Bombay or some place far off like that. There is so little I could possibly do at home; I would have to do nothing at all. But he says, “You have worked long enough. Can’t you live on your savings? We have this house, you can just live with us.”

I cannot make him understand that I would love to, dearly, to be back there, and that the hot summers don’t bother me any more; nor would I complain about the mosquitoes, nor about the self-important officials. But I can’t live there and not work, I can’t pretend to be a teenager living with his parents. My mother understands, but my father cannot.

“Come to San Francisco,” I say to him. “You know how pleasant it is. You can go to Stanford and Palo Alto and Berkeley and the bookstores and the libraries. I will take you to Monterey to see Steinbeck country. I can continue to work there, do what I have been trained to do and earn a living.”

“I can’t”, he says. “I’d miss my routine. And everything I am familiar with. I am too old to change now.” He is right, and we both know it.

Sometimes he says, “I have nothing to live for now. All I want is to see you and your sister and her little girl happy. I can die any day now.”

I want to tell him, “Father, I shall return. Just give me time. And no, I will not be coming back for you, but for myself. Because India means so much to me.” He does not know how much I miss the old Krishna temple. And the rain; the sibilant, sinuous, sinister rains of June.

I want to shout at him, “Shall I tell you of my dreams? I used to dream of America. Now all I dream of is a little village in Kerala. Where my ancestors lived. Where there is a pond, and cashew trees, and paddy fields, and grandfather’s house, and our family temple. And in the month of Aquarius, a festival at the Devi temple.”

I want to tell him about Kilimanjaro. About the Serengeti. About how I feel about America, alone amongst the thundering herds of wildebeest. About how I wish to go on pilgrimage, to Sabarimala, to Chidambaram, to Benares, to Rishikesh, to Manasarovar.

Instead I say nothing. I talk to him agreeably about world affairs and the weather. But one of these days, I must tell him the only thing I want from him. Father, I want you to live until I come back. I want to be there for you when you fall.

And I must quote Dylan Thomas to him:

“Do not go gentle into that good night…

Rage, rage, against the dying of the light…”

3500 words, January 1997

Winner, Honorable Mention, Katha Fiction Contest, India Currents, California. 1997

Life vs. Livelihood: the #WuhanCoronaVirus Dilemma

April 19, 2020

Lives vs. livelihoods in the time of the Wuhan Coronavirus

Rajeev Srinivasan

On April 14th, the prime minister told us that the Wuhan CoronaVirus-related lockdown will continue till May 3rd, subject to certain loosening of restrictions to be announced by April 20th on a case by case basis.

The PM has a very difficult set of choices, and needs to juggle many issues. There are three important considerations, in order:

- Lives

- Food

- Economy or livelihood

It’s an incredibly tough call. If you are lucky, all three can be managed. If not, the failures will be catastrophic. It’s likely that it is only possible to optimize any two; you cannot optimize all three simultaneously. But this is what resilience is all about: how can we manage the entire problem?

So far, we have concentrated on saving lives. That is not true of other countries, say the US, which arguably favored the economy over lives, figuring that there would be a certain number of casualties, as in the 50,000 deaths per year from the common flu. There the argument (which has taken on a Trump-centric culture war flavor) is over whether to dilute the lockdown.

It is almost self-evident that lives must be India’s first priority, because in a country like ours, with a creaking medical system and poorly regulated infrastructure, a pandemic could wreak total havoc. There was frightening talk of 500 million deaths.

That particular number came from someone soon unmasked as a person with a conflict of interest because he represents a company with test kits to sell, but practically the entire Western media was just waiting for a huge calamity, with Indians dropping dead on the streets in lakhs. They are startled, and find it hard to accept that there are only 500 or so deaths.

For a long time, data providers such as ourworldindata.org (https://ourworldindata.org/the-covid-19-pandemic-slide-deck) only published country-specific numbers of cases or deaths, whereas a more accurate metric for comparison would be cases/million and deaths/million. They recently started publishing this, and so has the Financial Times.

This data shows that India has done relatively well so far, which is nothing short of miraculous, and things can still go horribly wrong. At the moment, even though India’s first cases were observed as early as the end of January, that is 80 days ago, there has not been a catastrophic growth in either cases or deaths, although they are doubling every five to six days now.

How this was achieved is not entirely clear, and it probably has to do with both a) natural endowments of the country, and b) government interventions. Since so much is not known about the virus, it is so far unclear whether Indian weather (hot) or cuisine (spicy especially with turmeric and other known immunity-enhancing agents) or genes are at play.

It could also be the BCG vaccination against tuberculosis that we took as children. Nobody knows for sure. But the general exposure to pathogens because of weather, dirt, and squalor probably provides a certain level of immunity.

On the other hand, the government did take early steps, closing off China-origin travel, then international travel of all kinds, and finally the lockdown from March 24th. The resultant distancing from disease carriers surely helped flatten the curve, despite incidents like Delhi dumping migrant laborers on its borders, and the Tablighi Jamat event.

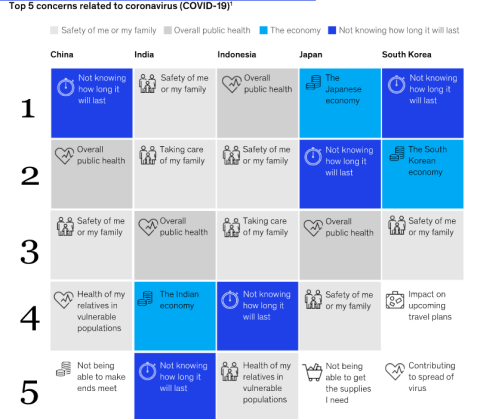

A McKinsey survey of consumer confidence in Asia from March 30th https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/asia-pacific/survey-asian-consumer-sentiment-during-the-covid-19-crisis?cid=other-eml-alt-mip-mck&hlkid=d222de540c0a4786bedbba46f3f1c0d6&hctky=1873873&hdpid=560ddc95-a00e-4648-a04a-c25075ace5e0 shows Indians are surprisingly optimistic about the impact of the virus: 52% of Indians think things will improve in 2-3 months, compared to 6% in Japan and 25% in South Korea.

Indians are also more concerned about their lives rather than their livelihoods, according to this survey’s findings. Incidentally, the medical focus may shift from the Wuhan Coronavirus shortly, as the monsoon is approaching, and recent endemic diseases like dengue and chikungunya may become the source of more deaths and hospitalizations.

But these results (assuming the survey is methodologically impeccable) hide two major assumptions: that there will be enough food to eat, and that people will be consuming (other) things. Neither is a given.

On the food front, it is clear that the stringent lockdown has affected the supply chain, which is unnecessarily long at the best of times. Too many intermediaries, all of whom need their profits. The net result is that the actual producer gets almost nothing for agricultural products, which also all ripen at exactly the same time, thus driving prices further down.

There are no facilities either for storage of produce (as in grain elevators in the US) or for value addition, as in turning tomatoes into ketchup. This means farmers may face ruin. As an example, there was a tweet about a farmer in Kasargod, Kerala who had 14 metric tons of ash gourd he had harvested. Fortunately the Horticorp responded to his SOS.

Food security has to be the highest priority now that there is a certain flattening of the disease curve. Apparently government-procured staples like rice and wheat are available in warehouses in substantial quantities, so that it is possible to provide free or subsidized grain and pulses to large numbers through the ration-public distribution channel. The BPL, below poverty-line people, are taking advantage of this.

They, and the working poor have been taken care of through free and highly subsidized rations available through this network; they probably will not be food-stressed, if they are daily wagers, maids, auto drivers, small tradesmen and so on. (Online direct benefit transfers to Jan Dhan accounts will help with small amounts of cash).

In this context, there is one group that has received almost no attention: those associated with Hindu temples. Since many of the workers in temples receive a pittance from the governments who run them, they generally survive on dakshina from the faithful. That source has dried up in its entirety.

Similarly, this is the season for temple festivals, and that has been entirely lost: so, for example, theyyam artists in Kerala, and the owners of elephants that take part in the festivals, are among those who will struggle to survive. Unfortunately, nobody seems to be paying any attention to these groups, who anyway live a precarious existence.

So far, there have been relatively few cases of real food distress. But that may not last if: a) all sorts of agricultural produce is not harvested, including for lack of workers, b) the supply chain is not working, c) the last mile that is the corner kirana store or vegetable stand is not open.

That last is a metaphor for the entire livelihood issue. As Professor R Vaidyanathan, formerly of IIM Bangalore, has argued, the informal sector is the real key to the Indian economy. It is likely to be affected because of a) razor-thin margins, b) lack of capital and credit, c) lack of supply.

This means ruin for some numbers of the lower middle classes, who are already shaky because of demonetization and GST (disclaimer: these are good policies, but they do hurt those from the informal economy). They who have been clawing their way out of poverty will become for all intents and purposes destitute, and join the bottom of the pyramid.

To avert this, there has to be a series of significant measures announced by the RBI and the Finance Ministry, aimed at livelihood. In some sense, it is best for the GoI to give them targeted grants as well as low-cost loans as well as a loan holiday.

Bankers confirm that instead of a loan holiday, the existing moratorium requires that the entire set of missed payments become due after three months; it would be much better to add these payments to the end of the loan with interest forgiveness so that the tenure of the loan is extended.

There are innumerable small businesses that will probably never come back to life, especially if people get used to the low-consumption regimen we have seen during the lockdown. For instance, people have done without fish and meat; without going to the movies; without driving around; without buying new clothes. Now that this is evidently possible, will it become the new normal? If so, what do you do with those turned into the permanently unemployable?

This last problem is something that must be faced by all nations, and I understand there is a movement in the US, for example, to accelerate the opening up of the economy as a prelude to a return to normalcy. But is it the old normal or some new normal? We don’t really know. Even Singapore and Japan, which had come through with flying colors in the earlier round, now face a new wave of infections and are forced to declare emergency shutdowns.

There will also be plenty of questions and recriminations in hindsight. Did Modi’s lockdown cause the Indian economy to fall apart? Did Trump’s alleged callousness cause the large number of fatalities in the US? Who knows? The fact is that the Wuhan Coronavirus (Covid-19) is one of those unforeseen things that has upset many cozy calculations.

Statistician and public intellectual Nassim Nicholas Taleb warned us early on in a one-page paper that there were so many unknowns about this virus that it’d be prudent to take extraordinary steps, even over-react. Maybe PM Modi erred on the side of caution, and made a reasonable decision under uncertainty given the data on hand at the time.

1550 words, 19 April 2020

#kerala and #wuhancoronavirus. unequal contest? #replug

March 26, 2020

my recent swarajya piece on how kerala has led the way (or not ) in dealing with the virus.

https://swarajyamag.com/ideas/kerala-in-the-time-of-coronavirus-what-helps-and-what-doesnt

#coronavirus #covid19 is there a #deepstate conspiracy, or did the Chinese do it all by themselves?

February 29, 2020

The fix is in: Stings in the time of the coronavirus?

Rajeev Srinivasan

The more I think about the COVID-19 pandemic, the more I am reminded of the great Paul Newman-Robert Redford movie The Sting (1973), in which an elaborate charade is run to gaslight and then relieve a mobster of a very large amount of money.

Because it just doesn’t add up. There are too many loose ends, all of which suggest that an Occam’s razor-type simple explanation may not cut it. There’s something fishy.

Information Warfare?

But first let me point out something remarkable: the role of Indians in what amounts to information warfare. There is the Hyderabad-based conspiracy theory site GreatGameIndia, which filed a series of sensational exposés, starting with

Coronavirus Bioweapon – How China Stole Coronavirus From Canada And Weaponized It

Among other things, they published stories about the Harvard University chemistry/chemical biology head who was being paid $50,000 a month by China, and a Chinese scientist and her colleagues at a level 4 high-security Canadian virus lab in Winnipeg, who was expelled for stealing samples.

Other Chinese were also accused of similar attempts to steal samples of deadly diseases.

Furthermore, there was the sudden, and suspicious, death of well-known virologist from the Winnipeg lab, Frank Plummer, while on a trip to Kenya.

Even if you discount all this quite a bit, there are too many things that just don’t add up.

Then there was the unrefereed, preprint paper published on 31 January on bioarxiv,

Uncanny similarity of unique inserts in the 2019-nCoV spike protein to HIV-1 gp120 and Gag by Prashant Pradhan et al, biomedical scientists from IIT Delhi, which bluntly states that the odd characteristics they found are likely to be man-made.

They found proteins very similar to those in AIDS in the surface ‘spikes’ on the spherical virus that enable it to target host cells. This was nothing AIDS-like in earlier coronaviruses and it makes it far more infectious.

“This uncanny similarity of novel inserts in the 2019-nCoV spike protein to HIV-1 gp120 and Gag is unlikely to be fortuitous”, says the paper. [Emphasis added]. This is ominous.

Chillingly, Chinese have been using AIDS drugs to combat the coronavirus https://greatgameindia.com/china-using-hiv-drugs-for-coronavirus-treatment/. Coincidence?

I have no idea if the IITD paper is correct (after a lot of pressure on social media, it has been withdrawn pending peer-review), but from a geopolitical perspective, it, and the GreatGameIndia exposés, raise large question marks about China.

This is also just about the first time I can remember that Indian groups have put forward compelling stories that have a material impact on the fortunes of a major rival like China. This is a good trend: let us not only be victims of information warfare, but also perpetrators.

But the core of the story is the question of how the virus came to be. There are three possible scenarios.

Was the virus was passed on to humans from an animal carrier?

It was a natural mutation passed on to humans. A carrier animal is unaffected but it is deadly for humans.

This was the original story and the most plausible, given the mode of transmission in other diseases, eg. the HIV virus jumped to humans from the green monkey in Africa.

Given the taste Chinese have for wild animals, and the fact that there is a ‘wet market’ with exotic meats in Wuhan, this makes intuitive sense.

Except that it appears that Patient Zero and most of the first infected had no link to that market.

Besides, nothing has been proven regarding speculation that it might have been transmitted via peple eating snakes or bats.

At this point, it appears that this simple and relatively comforting theory may not be enough.

A Chinese bioweapon?

There is the Chinese concept of unrestricted warfare (popularized by two colonels who wrote a book with that title) wherein nothing is off the table, literally nothing.

It is not hard to believe that they would pursue biological weapons, despite the fact that they signed a treaty abjuring them. Chinese also ignore other global treaties that they are party to (eg. the Law of the Sea).

There was a report about a blowhard Chinese general proclaiming that bioweapons are the best way to conquer other countries. Yes, buildings remains intact, only people die: the whole attraction of the neutron bomb too.

It’s entirely possible that, as the IITD paper alleged, gung-ho biomedical scientists thought they could use their new found gene-splicing skills (eg. CRISPR-Cas9) to induce HIV spikes.

Such an enhanced biological weapon would be terrifying to a targeted country (say, India).

No vaccine (except secretly with the Chinese) available. Panic, as lots of people die in the early stages even before the disease is identified. Unquarantined flight from epicenter, spreading it.

And then the virulence will die down relatively quickly, so that the conquest can proceed.

It is entirely possible that they created this weapon, and then it escaped accidentally and infected the Wuhan population.

This remains the most likely scenario.

A bioweapon ‘gifted’ to China?

There is an alternative possibility that frankly is a bit of a conspiracy theory, but it cannot be discounted.

There is a famous question: cui bono? Who benefits? Who has the motive and the means to commit any crime? Sherlock Holmes might pursue this angle.

Indeed, who has benefited from the coronavirus? If you look at it dispassionately, the US has benefited. They are in the midst of a general competition with China, and some would say there is the Thucydides Trap effect in motion.

Let’s look at what China is facing now: a trifecta with the Hong Kong uprising, the ongoing trade war, and now ‘instant decoupling’ as the rest of the world distances itself from China.

All of this is quite convenient for the US, and indeed some say they instigated the Hong Kong protests.

The decoupling, though, has the biggest long-term impact. China’s status as the factory of the world was already in jeopardy as wages rose there, and there is pushback (eg. the Huawei case) against the legendary Chinese habit of predation.

For instance, it is alleged that Intellectual Property theft by Huawei eviscerated and bankrupted the Canadian firm Northern Telecom.

All of a sudden, CEOs whose supply chain strategy was total dependence on China (eg. Apple’s Tim Cook) are looking like poor risk managers, as China manufacturing has ground to a halt. A second source seems imperative.

I don’t think anybody will ever go back to a China-only supply chain strategy, even if the ‘China price’ is attractive. Besides, near-shore manufacturing (eg. Mexico for the US) looks more appealing, as the carbon footprint of long-distance shipping becomes an issue.

Thus, the decoupling that the US had threatened as a punitive measure is happening much more broadly, with the possible effect of crippling Chinese GDP growth and creating a massive loss of face and loss of trust.

In passing, the brutality with which Chinese citizens have been treated (some had the entrances to their homes welded shut to prevent their escape; there were scenes of people being dragged from cars and assaulted) is likely to create a chink in Xi Jinping’s armor.

Thus the US had the motive to create a false-flag bioweapon and attribute it to China.

They also had the means. There are many reports of Chinese researchers in US labs stealing research (possibly with a little prod from Chinese intelligence or appeals to patriotism).

Imagine, then, that US military biomedical researchers created this little monster COVID-19, and then just left it around temptingly for Chinese researchers. Naturally, they would spirit it off to Wuhan (China’s only level-4 bio lab).

The rest is history. The Chinese had no idea the US had left some little trapdoor open whereby the virus would get out of control and go on a spree of infection. (Remember, in a different context, the Stuxnet computer virus that decimated Iranian nuclear centrifuges? The virus was spread by leaving thumb drives temptingly all around the place.)

Such an act would be diabolical, but the US Deep State has been known to do similar things before. Hewlett Packard printers, it is said, were bought by the Iraqi air defense agency. They didn’t know that the printers had chips in them that would be homing devices that announced the locations of targets to US fighter jets in the air.

Targeted assassinations are also par for the course. The American virologist who died suddenly in Kenya probably knew too much for his own good. So did Iranian nuclear engineers, as well as Indian space and submarine engineers who ended up in body bags.

We also know how Nambi Narayanan and his cryogenic engine project were crippled and delayed by 19 years with a fake Maldivian spy case. Fortunately Nambi Narayanan wasn’t bumped off.

The resourceful Deep State and what it will do to us

The Deep State is nothing if not resourceful. I remember in the 1980s, when it looked as though nothing could stop Japan from taking over the world. I am not sure exactly how they did it, but clever Americans weaponized finance, and brought Japan to a grinding halt.

What is truly diabolical is how somebody’s weakness is exploited to destroy them. The Chinese have this known weakness about pilfering others’ secrets, and the Deep State figured that out as their fatal flaw. This may well halt the Chinese juggernaut.

And just incidentally, Gilead Sciences has just announced they have a candidate vaccine. This is a sure-fire money-spinner, and it’s astonishing how quickly they were able to do this. No, I am not insinuating anything.

There is a lesson in this for India. In the wake of the Trump visit and the concurrent riots, it is worth remembering that India is also on a trajectory to challenge the US, and the Deep State is not going to sit by idly. Hark back to George Kennan on what the US does: it wants 50% of the world’s resources for itself. It does not brook competition well.

We need to think hard about how they will attack India.

One line of attack is already visible: continuous, vicious demonization of Hindus and Prime Minister Modi by pliant western media and politicans such as Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton and Elizabeth Warren, as well as free agents like George Soros.

There is a manufacturing of consent for the genocide of Hindus.

Hindus are demonized in terms not seen since the ‘yellow peril’ meme for the Japanese, or the depiction of Jews by Europeans bent on pogroms.

This is followed by induced riots and targeted violence by the device of Deep State’s friends inciting Muslim separatism and terrorism.

Remarkably, India may be able to control and absorb this threat because we are a flexible civilization that can learn, not rigid adherents to texts.

We have an 800 year history of dealing with the Muslim threat, and yes, we have taken a beating, but India is the only civilization that was able to fend it off. Persians and Egyptians, for instance, crumbled instantly.

There is a more insidious line of attack that may be more effective. It is a character flaw among Indians to be willing to betray the country for petty personal gains. Let’s call it the ‘Jaichand syndrome’.

Pretty much any bureaucrat or diplomat or politician is liable to sell India down the river in exchange for something as trivial a scholarship to (usually) Harvard for offspring, or a cushy post-retirement sinecure in some multilateral institution.

I am sorry to say they sell themselves for peanuts, not even large sums of money.

I predict this is the mechanism by which the Deep State will attempt to cripple India in a few years. Alas, they will probably succeed.

1970 words, 28 Feb 2020

#namasteTrump is there an afghanistan-PoK deal in the works?

February 23, 2020

Why is Trump coming to India?

Rajeev Srinivasan

President Donald Trump is preparing for a bruising battle later this year to be re-elected. So why is he wasting time on a trip to India?

Given Trump’s transactional nature, his principal agenda is re-election; for which he will make any deals. What might that deal be with India?

First, what it will not be. Given that Trump has blown hot and cold with friend and foe to create a trade surplus for America, it is startling that there is no trade deal on the anvil. In fact, his hard-nosed trade czar Robert Lighthizer isn’t even coming.

Yes, there is the relatively wealthy Indian-American electorate, but at about 4 million it is too small and too fragmented to make a difference. And by past form 70% of them are hard-core Democrat voters anyway.

So that’s not the attraction. Nor is it any particular need to get some brownie points with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s supporters. Given the easily-mollified Indian psyche, the spectacle of “Howdy Modi” was quite enough for that.

What, then, could be the rationale? What we have seen in the past is that Indian PMs on US visits sign a bunch of deals buying American stuff (it’s like a peace offering by a vassal to a Ming emperor). US Presidents on India visits bring a bunch of CEOs, also selling.

It’s not clear there’s any buying of Indian goods on the agenda. The ‘Make in India’ effort seems to have faded into obscurity, although India does have a small trade surplus with the US.

We also have to be careful about Americans bearing gifts. In 2005, there was a flurry of activity with sundry snake-oil salesmen flying in, glad-handing everyone, and waxing eloquent about how the proposed ‘nuclear deal’ was going to solve half of India’s problems.

In the event, not a single Westinghouse nuclear reactor ended up in India. Which, by the way, is just as well. The clean-up costs (and the fear of terrorists gaining access) make nuclear power unappealing. And then there was Fukushima and the slow-motion collapse of the industry.

So there’s nothing large in the offing in this Trump visit, except for a few billion-dollar purchases of helicopters and similar equipment.

And the Americans are no longer screaming loudly about India’s plans to purchase an S-400 anti-missile system from Russia, especially after formal NATO ally Turkey bought the same.

There is also some progress on the Quad, with the recalcitrant Australians apparently being invited to join Indians, Japanese and Americans in the next Malabar exercise.

The Quad, of course, is aimed at containing China, regardless of everybody’s disclaimers. Given Hong Kong, the trade war, and now the coronavirus, China is beginning to look a little vulnerable, and admittedly, this may well be the time to ram home the advantage in Asia.

But India needs the Quad just as much as the US, so there’s no need for the dog-and-pony show that the US President’s visit normally becomes. Especially his first trip after the impeachment circus.

Let us note with relief that Trump is also not making a hyphenated visit to Pakistan. Those with long memories remember that Bill Clinton, a charming rogue who hoodwinked us en masse into thinking he was our friend, made a hyphenated visit.

To give the Trump administration credit where it’s due, they have been generally helpful in international matters. They did help India in the UN Security Council when China and Pakistan were crying bloody murder about Article 370.

So where’s the quid pro quo? There’s no free lunch.

Let us also not delude ourselves with all those fine, flowery words about largest democracy and oldest democracy and all that good stuff. That’s strictly for the birds. Americans look after their national interests, period, and will sup with the devil, or any dictator, as need be.

Given the animosity towards India from the US Deep State, its media (NYT, Wapo, even the MIT Tech Review), and much of its Democratic political base (Exhibits A, B, C: Senator Lindsey Graham, Rep Pramila Jayapal, Rep Ilhan Omar), there will be no Indo-US love-fest.

Being a cynic, I can only think of one over-riding geopolitical objective.

Afghanistan.

Why? The Democrats will get their act together. They are not going to be as hapless as McGovern-Shriver (1972) or Mondale/Ferraro (1984). A Bloomberg or a Warren or a Sanders will be no walkover, and Trump will have to work hard to defeat them. What will work?

The one thing that will be a big hit with the voters is an exit from Afghanistan, after a fruitless nineteen years there, and countless lives and trillions of dollars spent. That can be the October Surprise. And what better than to get India to send the boots on the ground?

Let us note that Trump is going to sign a peace agreement with the Taliban on February 29th, immediately after the India trip.

Thus, I suspect, there is a deal that will play out, and not in public. Donald Trump wants to declare victory and run like hell from Afghanistan. But they cannot leave a vacuum there with the Taliban (a proxy for Pakistan’s ISI) quickly filling it, and the Chinese moving in.

India has firmly rejected proposals by the US that India should get involved in Afghanistan, although the ‘strategic depth’ Pakistan has craved in that country is a concern, especially as it continues to destabilize India through its astroturfed low-level insurgencies.

But what if there’s a sweetener on the table now? Despite posturing by insurgents, the situation in the Indian Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir is far more peaceful than it was before special privileges under Article 370 were removed.

The discourse on the Indian side, I have noticed under current Minister for External Affairs S Jayashankar, is no longer about accommodating Pakistan’s demands about the Indian territory of J&K, but about when the Pakistan-occupied part (PoK) will be absorbed into India. This is a quantum leap from the earlier, diffident Indian position.

India has always claimed the entirety of Jammu & Kashmir, based on its formal accession to India, and on the UN Security Council’s resolution that invading Pakistani troops must withdraw.

What if the quid pro quo for Indian involvement in Afghanistan is that the US helps India eject the Pakistanis from the part they are occupying? Among other things, that opens up a land border for India to Afghanistan.

More interestingly, this would be a big blow to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship Belt and Road Initiative, because that passes through Pakistan-occupied parts of Jammu & Kashmir (PoK), over India’s strenuous objections about its sovereignty being affected.

That is not going to be easy, but if Trump really needs to extricate himself from Afghanistan, there is a price to pay. India should drive a hard bargain. He needs India more than India needs him now.

This is Trump’s best chance to trounce China, and he needs India and others to do it. We remember how America’s best and brightest fended off the Japanese challenge some 30 to 40 years ago by weaponzing finance. Maybe in China’s case, it is a virus.

Or maybe Trump has just lucked out.

China looks more vulnerable now than it has for some time. If I were a conspiracy theorist, I’d wonder, cui bono?, given all the problems they are facing.

There is a forced decoupling of supply chains. US manufacturers such as Apple are likely to reduce dependence on Chinese suppliers. Chinese tourists are being treated with suspicion. Their GDP will take a direct hit, probably shrinking, as Japan’s has.

Under the circumstances, I would not be surprised if, away from the pomp and the parades, a secret pact were to be signed linking an Indian role in Afghanistan (the US’ interest) and US support for the recapture of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and the subsequent dissolution of Pakistan into three-four statelets (India’s interest).

This would mean there’s more than meets the eye in Trump’s first visit to India.

1350 words, 21 February 2020

#replug. deconstructing #romilathapar, symptom of #jnu dysfunction

November 19, 2019

https://www.deccanchronicle.com/360-degree/080919/fuss-over-emeritus-who-is-shilling-for-thapar.html

#replug: Why 2019 is a pivotal election year

January 30, 2019

https://www.rediff.com/news/column/why-the-2019-election-is-pivotal-for-india/20190128.htm

The 2019 election gives the Indian public the same choice: Between growth and oligarchs (or, in our case, dynasts and crony capitalists).

If we chose wisely, well and good.

If not, well, we have the Nehruvian Rate of Growth and massive corruption to fall back on.

In a large sense, it is a choice between the India of the Lutyens elites, and the Bharat of the real citizen, says Rajeev Srinivasan.

When the parades are over and the curtain has come down on the Republic Day celebrations, there is the question of what this entire spectacle actually means.

What exactly are we celebrating?

What is the relevance of the Republic?

What has been accomplished in 70 years of the Republic?

What remains to be done?

What has the ‘rule of the public’ failed to do?

Have we, the public, messed up?

… deleted

i wrote the attached in november, when the ICJ win over britain was being trumpeted. i sent it to an editor who said he’d publish it, but didn’t: i don’t think it was out of fear, but out of other, more mundane considerations, like i’d fallen off his roster of columnists for lack of activity. anyway, i thought it lost timeliness.

but now i think it may add a little oil to the current fire about foreign policy. my general thought is that though it was well begun, the PM’s foreign policy has now lost its way. the MEA is doing too much low-level stuff of no great value. i’ve been urging @vijay63, the BJP foreign policy cell head, repeatedly on twitter to step up and make sure there was triage, and that real foreign policy issues are paid attention to, and not trivialities.

also, i was right in forecasting that the chinese proxy party in nepal would win, and that nepal would fall into china’s lap.

here’s the original copy:

India’s foreign policy: are we getting outmaneuvered?

Rajeev Srinivasan

There was much celebration over the fact that the Indian candidate for the International Court of Justice won a hard-fought victory over the British candidate. Since this is for a term of nine years, Justice Dalveer Bhandari will, one imagines, champion India’s causes there, including the pending issue of Kulbhushan Jadhav, jailed on false charges in Pakistan and threatened with execution.

It is a signal victory for Indian diplomacy, and those at the UN, especially mission chief Syed Akbaruddin deserve to be congratulated. It is said that despite strong opposition by China and Pakistan, there was support from the Arab world, and also from Europeans who are peeved with Britain over Brexit. There is, however, the question of how many silver bullets India would have used up in this election, and whether in the long run it was the optimal use of foreign policy resources.

In the meantime, at least three other events took place that suggest that India’s position in foreign affairs is not as strong as it could be. The first is the release, just a few days before the tenth anniversary of the 11/26 attacks on Mumbai by Pakistani terrorists, of the alleged mastermind, Hafiz Saeed. The second is the successful intervention by China in the Rohingya affair. The third is the elections in Nepal, which is seen as a proxy battle between friends of Indian and friends of China.

But back to Hafiz Saeed. He had been under house arrest for some months (although he suffers no great hardship in his Lahore mansion) and the US had placed a reward of $10 million for information leading to his conviction. The Lashkar-e-Toiba founder was released when a Pakistani court found that he was not a threat. The US made its customary distressed noises, saying this act would have “repercussions on bilateral relations”.

The very fact that, thumbing its nose at India just before the anniversary of 26/11, Pakistan felt free to release Saeed and not rearrest him on further charges (as the US demanded) suggests that there is a tacit understanding between the two countries. It is back to business as usual, although the strong words from President Donald Trump last year, and the sidelining of much of the Deepstate, had led us to expect that there would be a sea-change. Sadly, it does not appear to be so.

This is despite the glad-handing and bear hugs between Trump and Prime Minister Modi and the recent visit of the US Secretary of State Tillerson, the Malabar joint naval exercises, and all the talk of the US-Indo-Japan-Australia Quad. All of that is helpful to the US in its competition for China, but it’s not clear how the US is willing to go to bat for India in its concerns: which means we’re back to square one.

On to the Rohingya crisis. The Lutyens types made many noises which amounted to wanting to settle large numbers of them in India (by the way, I guess nothing has happened about deporting those illegally settled in Jammu and in Hyderabad?). But there was nothing constructive about ending the crisis. Now it appears as though China has brokered a deal whereby Myanmar will take back those who had fled, and rehabilitate them. The details are not clear, but the big picture is that benevolent China, the neighboring superpower, has been able to persuade two Asian countries to do something sensible.

Now why didn’t India do this? After all, China has no borders with Bangladesh, nor did it help it through a painful civil war. India also has a fair amount of goodwill in Myanmar. Instead, the Chinese have rescued Ang San Suu Kyi from a tight spot: she was getting to be a little persona non grata among the western countries that had championed her. There will surely be a quid pro quo for China.

The third is Nepal’s elections. Early indications are that there is a lot of money being spent, and no prizes for guessing the money is coming from China. In effect, the elections are being seen as a proxy fight between India and China. Given prior form in the subcontinent, where India is seen as a bit of a Big Brother, chances are that the election will go China’s way.

In addition, something that worries me is the fact that the Minister of External Affairs, the kindly Sushma Swaraj, is constantly being swamped on twitter by Pakistanis seeking medical visas. And being the compassionate soul that she is, she does respond to them and help them. My concern is moral hazard: by encouraging this behavior, India gains nothing; instead, let them go to China or Saudi Arabia.

800 words, Nov 27 2017

#replug #doklam is not the end game: only the paranoid survive

September 2, 2017

this piece of mine appeared on swarajya.com on 29 aug at https://swarajyamag.com/defence/premature-celebration-about-doklam-remember-only-the-paranoid-survive

do not lower our guard. i fear that the chinese, a bit surprised by modi standing up to them, will now activate their sleeper cells all around, leading to

a) riots: like the Jat, Patil, JNU kanhaiya riots

b) accidents: train crashes, floods,

c) terrorism: more incidents across the border, in Jammu Kashmir, including stone throwing support for holed up terrorists, and this will spread more broadly

d) cybersecurity: mysterious collapses of financial system, etc

hans, like a woman scorned, will hit back hard to avenge their loss of face.

the poisoning of modi in xiamen during BRICS2017 is not unlikely. i said this in my draft of this piece, but the editor didn’t agree.

going beyond #data, to #intuition, #connections, rethinking #epistemology in indian terms

August 3, 2017

this piece was published by swarajya magazine in its august 2017 issue. it is online at https://swarajyamag.com/magazine/-going-beyond-data-on-intuition-knowledge-and-the-connectedness-of-things

Are we being unfair to Dhume? Or Dhume to me?

July 26, 2017

Let’s talk about who said what when, and priority dates, then

Rajeev Srinivasan

As a columnist in the Indian media for over twenty years, I have had several of my ideas copied without attribution by others, and I have always looked at this with mild amusement. If you put things out there in the public domain, there is always the chance that this will happen, and it may not even be such a bad thing. This is how ideas propagate, and all of us stand on the shoulders of others whose works we have read and unconsciously internalized.

Thus I was not particularly surprised by a column on wsj.com by Sadanand Dhume, titled “India’s Incredibly Shrunken Presidency” https://www.wsj.com/articles/indias-incredibly-shrunken-presidency-1500573655 . Several points made by Dhume I agreed with, and the structure of the piece appealed. It bemoaned the fact that non-politicians had very few chances to become President of India, and named a few professionals who would be, in a fairer world, serious candidates for the post. It then expressed regret that few Presidents nowadays were of the calibre of some of the stalwarts of the past, naming some of the worst examples. I read this piece and left it at that.

However, someone who was struck by some similarities with a piece I had written a month earlier, “E Sreedharan for President” http://www.rediff.com/news/column/e-sreedharan-for-president/20170616.htm on rediff.com put together a brief comparison chart that showed several similarities between my piece and Dhume’s piece. The BJP’s Amit Malviya tweeted about the similiarities, and here is his tweet: https://twitter.com/malviyamit/status/889723345641512962. The screenshot doesn’t capture the entire image.

That got me curious about these similarities, so I read both pieces carefully. There were differences: I wrote in general terms in June, requesting that the BJP nominate a non-politician. Dhume wrote in July, after the election, suggesting that a specific individual, Shri Ram Nath Kovind, the new President, was unworthy.

But overall, I was struck by the fact that the structures of the two pieces were almost identical: general concern about the role of the presidency, desire for non-politicians, etc. There were five or six clear similarities between the two. And I found a couple of others: both had mentioned the bathtub cartoon lampooning Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, and while I dreaded some ‘dreary political apparatchik’ being chosen, Dhume called Kovind a ‘humdrum politician’. All this was interesting, but nothing of great substance.

However, this morning, I was directed to a piece by Dhume, “How the BJP’s Smear Machine Works: A Personal Story” https://medium.com/@Dhume01/how-the-bjps-smear-machine-works-e6aeb0fca78a . Apparently, Dhume feels there’s a conspiracy against him, and in passing, that I am guilty by association. I think he’s wrong on both counts. He wrote a point-by-point response which I feel compelled to respond to.

In addition to some general comments, Dhume suggests that there is a “a clear difference in our prose styles”. I am not quite sure about this, because looking at it casually, we both write passable prose, that’s about all.

Dhume makes a point of going through each of the six suggested similarities in the chart, and asserts that he could have arrived at them on his own, and he quotes his own earlier writings in July 2015 and in 2012.

But where my mild amusement turns to mild annoyance is when Dhume, choosing his words carefully, says the following:

“I’m not using these examples to claim that Srinivasan, or anyone else, lifted the idea of writing about the merits of India elevating a non-politician from my 2015 column”….

“Once again, I’m not accusing Srinivasan of plagiarism because he happened to make a similar observation to the one that I made in a column two years ago, or in a widely shared tweet six months ago…”

“Ironically, if I used exactly the same examples as in the graphic I could accuse Srinivasan of plagiarizing my earlier work”…

Graciously, he continues, “Of course, this is preposterous. I have no reason to believe that Srinivasan did not come to his views about the decline of the Indian presidency independently”.

Nice wording, reminds me of (in a small way) “I came to bury Ceasar, not to praise him”. Damning with faint praise, I believe they call it.

So it appears to be a claim about primogeniture, so to speak. Unfortunately for Dhume, I can point to another of my columns from ten years ago, which I had referred to at the start of “E Sreedharan for President”: from July 2007, http://www.rediff.com/news/column/rajeev/20070723.htm “A Whiff of a Manchurian Candidate”. Almost every one of the points Dhume elaborates on was elucidated there. So Dhume stands little chance of accusing me of plagiarizing from him because this was written ten years ago, much before his own work that he quotes.

Here are the points Dhume made in response to the chart:

- Mostly mediocre politicians. I said in 2007: “The ceremonial leader of the country, which the President is, should really not be a politician… What India needs are leaders, intellectuals and others who can inspire the citizenry to dream and to aspire to greatness.”

- Jagdish Bhagwati and other potential candidates. Here are my suggestions from 2007, apart from O V Vijayan and E Sreedharan: “N R Narayana Murthy or Ratan Tata or Lakshmi Mittal or Azim Premji… K P S Gill,… Jagdish Bhagwati,… C K Prahalad,… Arundhati Ghose,… Fathima Beevi,… Vandana Shiva”. Yes, there are/were many deserving candidates. Ratan Tata is also one of Dhume’s suggestions, along with Rahul Dravid (I would never suggest a cricket player). By the way, I think Jagdish Bhagwati may be a US citizen, in which case he’s not eligible for the post and both of us would be wrong.

- The presidential palace. No, I didn’t say anything about this in 2007, and yes, 300 acres or 340 rooms just suggests the place is huge, a place of unimaginable privilege

- Excellence of past Presidents. I said in 2007: “So far as I can tell, none of the politicians who held the position particularly distinguished himself.” The point is obvious, and whatever phrases we used, both Dhume and I basically said that.

- Kalam and Radhakrishnan as good Presidents. I said in 2007: “Kalam, on the other hand, certainly stood out. This is quite possibly because he was a working engineer, not a politician… Perhaps the scholar Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan was a good President, for he was a towering intellect”.

- Dynasty loyalists. I said in 2007: “The problem is that ….the Congress – which cannot think beyond the interests of the Nehru Dynasty… are not particularly thrilled at the prospect of an activist President. They would much rather have someone who will do what they are told. This may well be a reason for choosing Prathibha Patil…”

It’s rather clear that the prior art argument doesn’t work very well, because almost all the points made were covered by me either in 2007 or 2017 before Dhume’s 2017 piece. And the laws about copyright and ‘fair use’ are such that it is acceptable for someone to use another’s ideas for limited research and educational purposes.

Therefore let me grant that I have no reason to believe that Dhume is not capable of arriving at all these ideas by himself, which seems to be crux of his argument. Hey, I can do “damning with faint praise” with the best of ‘em.

But there is also the dictum that “plagiarism is stealing from one person; research is stealing from many people”. In these days of efficient Google searches, and crowdsourcing on Twitter, it is astonishing how much one can dig up through due diligence, and one may unconsciously internalize what one read somewhere.

As a non-professional journalist, I have had the luxury of having consistent opinions over time, and I have suffered for it. For the longest time, I was a complete outlier. Then I was kicked off one newspaper not for what I wrote, but because the opinion editor didn’t like my political perspective. I stopped writing for another because the sub editor, who disagreed with my perspective, made it clear through unreasonable demands that he didn’t want me there. So I’m not about to change now. But there has long been a Leftie stranglehold on opinion, which basically prevents any dissent; and that extends to their online acolytes on Twitter and Facebook. They have been masters of ‘manufacturing consent’.

Therefore if Dhume feels that there is a Hindutva Troll Army [sic] after him, I sympathize. Personally, I don’t know anything about this, and they are all big boys and can take care of themselves.

#senkumar episode: #FoE censored, #commie #vendetta, #jati bias, too. bit like #dreyfus

July 16, 2017

didn’t occur to me when i wrote this article, but senkumar situation is a bit like l’affaire dreyfus in france: he’s a possible victim of religious discrimination. those of the communist religion do whatever they can to hurt hindus. this article was published on swarajay.com on 16 jul 2017 at https://swarajyamag.com/politics/is-the-hounding-of-former-kerala-dgp-t-p-senkumar-a-communist-witch-hunt

i had written in 1998 about l’affaire dreyfus and its relevance to us today. there is nobody to stand up for a wronged man. dreyfus was attacked because he was a jew. i think senkumar is being attacked partly because he’s an ezhava. and we have no emile zolas to say j’accuse. http://www.rediff.com/news/1998/jul/23rajeev.htm

The dangers of #bigdata and #junkdata. Similar problems with #AI, too. #weaponsofmathdestruction

July 10, 2017

this book review was published in Swarajya magazine, March 2017. it is not online, so here’s my actual copy.

lately, i’ve been seeing a lot of people swear by ‘data’. this is another shibboleth with terrible implications. the west has the vanity that by reducing everything to data they can arrive at the truth. that is not true. data becomes information only when contextual information is supplied.

besides, there are problems with ‘fat tailed distributions’. we assume, implicitly, that the phenomena we study are under the gaussian bell curve on normal distribution. if they aren’t, and are fat tailed, then what we think are unlikely events will happen far more frequently than we thought: thus black swan events.

the other huge problem is the unconscious assumption that ‘correlation = causation’.

we mess up on all these fronts.

what i call ‘junk data’ is data with incorrect assumptions that has been fed into computers, which will produce circular reasoning that ‘proves’ the assumptions correct. there are also heavily biased data sources that ignore inconvenient data points.

briefly, excessive dependence on the infallibility of computers is a bad idea.

i wrote a companion piece to this in swarajya, on the ethical problems of bias in data selection for AI. https://swarajyamag.com/magazine/fatal-flaw-in-ai-the-robots-will-probably-be-as-biased-as-their-masters

The Danger from our Over-Reliance on Computers and Big Data

Rajeev Srinivasan (Book Review)

Can we trust computers? The evidence is mixed. Those in the business have seen enough ‘kludges’ and bugs that they would, if they were honest, be suspicious of a lot of things spewed out by computers. But do the infernal machines work, more or less, most of the time? They in fact do, and they do useful things, too. It is now possible to mathematically prove at least the core (or kernel) of operating systems, but on average we have to take things on faith.

The average person on the street, however, is often misled into thinking that anything that comes out of a computer must be true, because after it all, it has the weight of all those white-coated types chanting mysterious incantations or whatever that you see in the movies. So if the computer tells you your credit score is a tad low at 500, you take it in all humility and internalize the idea that you are a bit of a deadbeat who can’t get loans.

Not to be a neo-Luddite, but our excessive dependence on computers is a bit worrisome. Our faculties as a species may be getting eroded. For instance, all of us used to do arithmetic in our head, until calculators came around. We used to navigate ourselves, until Google Maps appeared. There was a controversy over a 2008 article in the US monthly the Atlantic “Google Is Making Us Stupid” because now we don’t need to know anything, as we can look it up.

Unfortunately, this is coming precisely as computers are getting smarter. All those chess, Go, and poker players who have been bested by computers can tell you that. In fact, we now have to worry about the ethics of artificial intelligence and self-driving cars, as I mention in a companion piece in this issue. At least we think that’s in the future, but this book, Weapons of Math Destruction (Allen Lane/Penguin Random House, 2016) by Cathy O’Neill, a PhD mathematician-turned-data-scientist, suggests we are already feeling some of the deadly effects of Big Data.

A part of the problem comes from the confusion of statistical correlation with causation. The computer models make assumptions – for example that a broken family is associated with increased tendency towards violent crime – which are in the bowels of the algorithm, and are opaque and cannot be questioned by their victims. These proxies may not have a causal relationship with the outcome, but their use is widespread. A recent study by Daniel Hamermesch et al suggests there is a correlation in the US workforce between race and laziness, but undoubtedly, it will be taken to mean causation that blacks and Hispanics are inherently lazy precisely because they are blacks and Hispanics.

O’Neill’s villains are the big algorithms that increasingly run our lives. In a dystopian vision, she produces example after example of big pieces of software that have become a sort of Deep State, one whose workings are incomprehensible except to the code-jockey boffins who run them; and said boffins often have no idea of the devastation they can wreak on individuals and society.

We are generally familiar with the trading software that has caused ‘flash crashes’ and the algorithms that led to the sub-prime lending debacle in the US. But O’Neill (who had a ring-side view of the market meltdown as a quant jock at hedge fund D E Shaw) points out that that there are several others that have equally sinister outcomes, often because there is a self-fulfilling prophesy – people who are deemed undesirable by algorithms in fact become undesirable as a result.

O’Neill starts with a rating scheme for convicts called LSI (Level of Service Inventory); unfortunately, says she, the parameters used to rate them, and the questions in the questionnaire, are biased against the poor and especially against blacks. Thus unemployment and criminal convictions among friends and family seem reasonable enough questions, but they end up giving them longer terms and likely greater difficulty in finding a job upon release. This creates a vicious cycle.

Then O’Neill goes on to several other case studies, all of which may seem innocuous enough to begin with. But we begin to succumb to total dependence on the ratings spewed out by algorithms, the connection with reality begins to recede. The software guys doing the coding may have no idea of whether the assumptions they are making are appropriate. And the field guys who do know that stuff will soon be defeated by the complexity of the algorithms.

One result is the Black Swan effect that Nassim Nicholas Taleb wrote about so evocatively. Events with very low, but non-zero, probability will soon be excluded from the calculations, with the result that when such events occur (as they did in the 2008 meltdown) the entire edifice on which the algorithms rest will crumble catastrophically.

O’Neill talks of “haphazard data gathering and spurious correlations, reinforced by institutional inequities, and polluted by confirmation bias”. In addition, she wonders if “we’ve eliminated human bias or merely camouflaged it with technology”. She talks of “pernicious feedback loops” that lead to “toxic cycles”, and she concludes that these are the mathematical analogs of Weapons of Mass Destruction, hence the title of the book.

As examples, O’Neill offers up several algorithms. One is used to rate schoolteachers, which seems to grossly distort the incentives for teachers to focus largely, or entirely, on test scores, thus devaluing various other things a good teacher can offer: such as inspiring students, or taking time with a slow starter.

Another is the pernicious role played by a US News and World Report ranking of colleges, which has outlived the magazine itself. Apparently an objective measurement of the ‘quality’ of the college, this metric has now become so widely adopted that colleges focus exclusively on the fifteen parameters it considers. So much so that they went on a spending spree, building stadiums, grand campuses, attracting star football players, and so on. But college fees were not part of the metric; and these soared, as well.

Today, toxic student loans are a huge overhang on the US economy, as big as the bad mortgage problem. In addition, entrepreneurs created rip-off private for-profit colleges

which deliberately targeted poor and military-veteran students, as well as non-whites. Again, clever advertising techniques using Big Data allowed these colleges to sell essentially useless but expensive, loan-led ‘education’ to these people.

O’Neill suggests that greed is a major factor. The folks over on Wall Street who have been making up ever cleverer mathematical models to make money often don’t realize that money comes from screwing over real people, as was the case with sub-prime mortgages and the related credit-default swaps and Collateralized Debt Obligations. Or even if they do, they don’t care. She points out that despite major convulsions, in large part the big Wall Street firms and banks and hedge funds did all right, often at taxpayer expense.

O’Neill goes on to give a litany of other examples of malevolent data exploitation, for instance in hiring, loan processing, worker evaluation, voter targeting and even health monitoring. It’s chilling to think of how these will play out when applied to the relatively trusting and naïve populations of rural India. These algorithms, which are “opaque, unregulated and incontestable”, can be truly weapons of mass destruction. They take your privacy and individualism away from you, and whatever they decide about you, you have no appeal. Truly a frightening Big Brother scenario.

1250 words, 10 February 2017

Mr #Modi goes to #Washington: there will be slim pickings. #india low in deal-making list

June 24, 2017

this column was published on rediff.com at http://www.rediff.com/news/column/modi-trump-meet-why-i-have-low-expectations/20170624.htm

my rediff.com piece http://www.rediff.com/news/column/e-sreedharan-for-president/20170616.htm

i mean who else? which captain of industry hasn’t lose his/her sheen lately? and please don’t talk about sportsmen. and we don’t even have great writers any more. arun shourie would have been a great president, actually, but he seems to be on a self-destructive tear these days for reasons unknown. other than him, almost all journos are dicey. has to be an engineer, as we have no scientists worth the name. or nobel-class research professors.

this was written for rediff in 2012. i’m not at all sure things have improved at all in the last 5 years. RTE has become an increasing nightmare, and unfortunately, the MOOC revolution turned out to be rather less impressive than i thought at the time, although i still think on-line self-paced education is a great way forward for india.

and here’s the result: not one (but several chinese) universities in the list of those creating US patents. (a pretty good proxy for R&D, although not necessarily for innovation). http://www.academyofinventors.com/pdf/top-100-universities-2016.pdf

http://www.rediff.com/news/column/rethinking-education-in-india/20120510.htm

http://www.rediff.com/news/column/is-the-future-of-education-leaving-india-in-the-dust/20120516.htm

this piece appeared on abpnews at http://www.abplive.in/blog/india-no-country-for-children-and-women-537057 on june 11th.

the original content i sent them was the following:

The news about the appalling murder of a baby in Gurugram was startling in the extreme. News reports say that the 8-month old baby and her 19-year old mother were abducted by three men in an auto-rickshaw. The mother was gang-raped by all of them, and when the baby bawled, one of the men casually picked her up and threw her on the concrete divider on the road, presumably wounding her mortally. Then they abandoned mother and baby, and drove off.